STANDING AT THE EDGE OF THE RIVER, CAPTAIN STEVE MAHAY CAN FEEL THE ENERGY COURSING THROUGH THE SUSITNA RIVER AT HIS FEET. AFTER FORTY-PLUS YEARS SPENT ON ITS SLATE-GRAY WATERS, HE UNDERSTANDS IT; THEIR RELATIONSHIP IS ONE THAT SEEMS UNBREAKABLE. WHILE MOST VISITORS TO THIS AREA FIND THEMSELVES DRAWN TO THE TOWERING BULK OF DENALI IN THE DISTANCE, MAHAY FEELS THE PULL OF THE RIVER. AS THE YEARS FLOW BY HIM, HE SOMETIMES HAS BEEN TEMPTED TO SLOW DOWN, BUT THAT ISN’T VERY LIKELY. HE JUST WANTS TO GET BACK OUT ON THE WATER.

He was only twenty-four years old and fresh off a stint in India with the Peace Corps when he got a crazy idea. He would drive his Volkswagen Super Beetle from his hometown of Sarasota Springs, New York, to Alaska. It was 1972, and the Open to Entry homesteading program offered free land to anyone willing to settle in the state. It seemed like the perfect way to give him what he craved most, solitude and a chance to escape from the grip of civilization. So with $240 and all of the gear he owned, he headed towards Anchorage. Once there, he was faced with two paths to choose from: live by the sea outside Homer or in the interior, near the village of Talkeetna. “Since I didn’t know much about the ocean, and could not afford a boat, the choice was easy,” says Mahay.

Talkeetna in 1972 was a quiet backwoods outpost, rarely visited by anyone but hunters, trappers, and miners. That’s what drew him to the area; he loved running a trapline. Ten miles out of town, Mahay and his wife Kris jumped off the Alaska Railroad train at Mile 233.5 and headed into the bush. The plot they found was on top of a bluff near the Susitna River, with stunning views of Denali when she poked out from behind the clouds. Eschewing modern conveniences, they soon felled 65 spruce trees using only an ax and bucksaw. The resulting 14-x-16-foot cabin with no running water or electricity would be their home for five years. He spent the winters trapping. It was their only income.

After forty-plus years spent on its slate-gray waters, he understands it; their relationship is one that seems unbreakable.

The search for more efficient ways to get from one point to another has always driven innovation. It was no different for the Mahays. The 10-mile trip into town was pretty simple in the winter when the river froze, and they could dog sled right into downtown, but the summer was a different story. “This was before ATVs and such; we had to pack everything in. The two-and-a-half-hour trip one-way was not fun, especially when you have to haul several hundred pounds of supplies,” says Mahay. “So when I heard about the idea of modifying an outboard motor with a jet instead of a prop, it got my attention.”

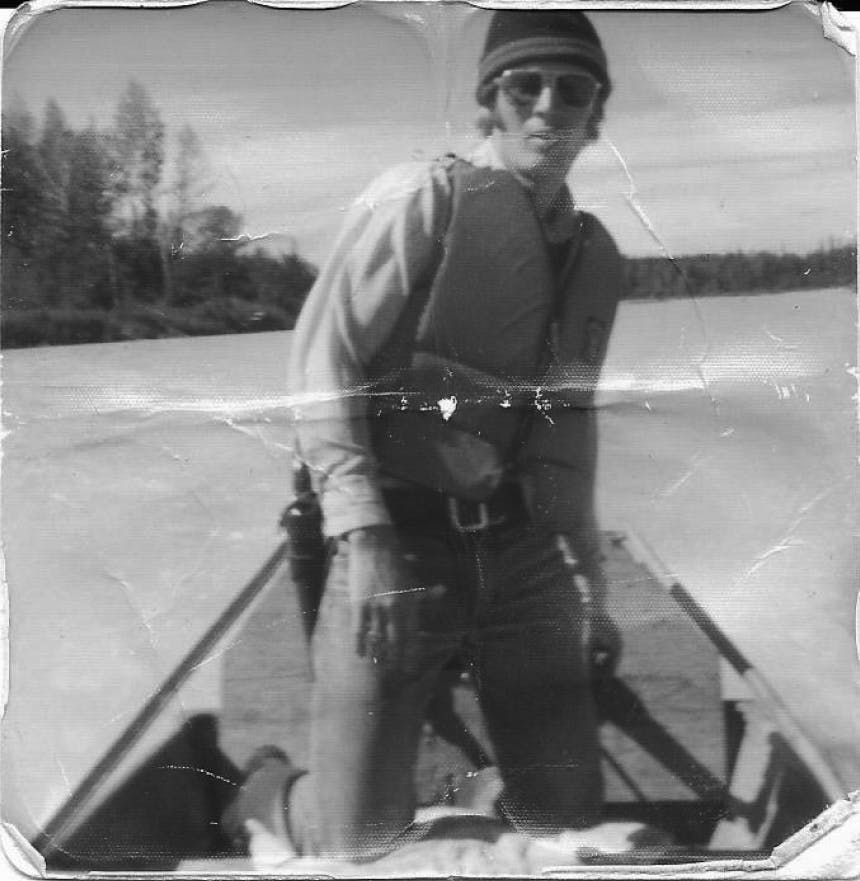

Never mind that in 1975, no one was running boats on the Susitna due to the inherent dangers: swift currents, a continually changing channel, and hidden hazards that would rip props right off. A boat would cut their travel time to Talkeetna in half and quadruple their carrying capacity. Mahay bought a 16-foot Jon boat and equipped it with a 20-horsepower Mercury engine and converted it with a jet outboard and started running the river. It was challenging. The silt-laden river flowed around ten miles an hour, the channel was continually changing, and underwater snags could yank a boat under in minutes.

After a couple of months, he decided to offer his services to others needing transportation. A sign hanging in the gas station advertised Mahay’s Riverboat Guides. The owner would call him on a CB when people showed up, mostly prospectors, hunters, trappers, fishermen, and residents that lived in the bush surrounding the town. The business started to grow, but trapping was still his main job.

"These rivers are not ones to be played with, things can get dangerous quickly if you don't know what you are doing...Learning how to navigate them correctly is a skill that's learned over time with lots of mentoring. You must be able to read the surface for any trouble coming up."

By 1977, two things happened to bring Mahay out of the bush. His wife was pregnant with his first son (he has three), and river running was becoming a full-time endeavor. “The word was getting out that we could take you into some un-foraged locations,” says Mahay. The move into their log cabin with running water, showers, and electricity was a welcome change.

That was also when he decided to upgrade to a bigger boat. He bought a twenty-four-foot inboard jet boat that could haul six people at a time. His boat only needed a few feet of clearance under the surface and could rip over the water hitting speeds of fifty miles per hour while being able to turn on a dime. His clients, mostly sport fishermen at that time, would come in for multiday trips where Mahay would take them further and further up the previously unrun river. Every day was a new adventure as he navigated the channels of the three rivers around Talkeetna.

Over the next decade, as more sportspeople showed up each season, Captain Steve grew his fleet of jet boats. He started to train others in the crucial skills needed to safely run the rivers, which took time and patience. “These rivers are not ones to be played with, things can get dangerous quickly if you don’t know what you are doing,” he says. “Learning how to navigate them correctly is a skill that’s learned over time with lots of mentoring. You must be able to read the surface for any trouble coming up.”

Due to his unique skill set, he and his team became the first persons called for a rescue on the rivers. Over the years he extradited hundreds from sticky situations and won several commendations for his work, while also fishing out his fair share of deceased persons. Life moved forward, his business was doing well, and his family was thriving in the land that had called to him years ago.

But always the itch for something new drove him. He would take boats further upstream, exploring and opening new routes, much like his childhood heroes Lewis and Clark had done almost two centuries before. In 1985 he decided to see if he could take a boat through Devils’ Canyon’s entire stretch on the Susitna River. A twelve-mile-long gorge loaded with class six rapids, it had repulsed all that had tried to run it, including an Army Special Forces team that had to be rescued when their boat sank. Every other jet boat that had tried had sunk too. Many thought it was impossible.

He was nervous enough beforehand to board up all the front windows of his twenty seven foot jet boat and fill the hull with foam. That way, if the boat sank, he might be able to salvage it at the end of the canyon, provided he survived going into the water. Wearing a full dry suit, a life jacket, and helmet, he gunned the four hundred horsepower engine and pointed his boat into the channel and headed upstream. It took all of his skills and a little luck to make it out the other end. As he navigated through ninety-degree corners and tight slots, he had to pilot by the seat of his pants. He almost went under when he smashed into a canyon wall and was flung to the deck, losing three teeth. When he made it to the end, he was astonished that he had done it and overjoyed. “Some of those slots I had to get through the boat was raised at a forty-five-degree angle upward, I was boating uphill, how I made it through it I don’t know,” he says. Only he and one other person have ever successfully run the river. His ascent of the Talkeetna Canyon in 1991 has never been successfully replicated.

A year-and-a-half ago, he sold the business to his oldest son, Israel, who was born in the cabin in the woods—raised on Steve’s knee he learned how to steer a boat almost before he could walk. These days the business is dedicated to tours of the rivers that were once untamed. His fleet has swelled to ten boats of all sizes that ferry adventurers at 35mph all summer long on a variety of trips.

At seventy-three years old, he still runs the rivers, maybe not as much as he used too, but it’s something that he can’t give up. The thrill of gunning a motor and heading out never grows old. When he goes around a curve and sees a Grizzly Bear or moose at water’s edge, he feels that tug that drew him north all those years ago. The one that led him here today.