There is much to consider, when one envisions the basic necessity of water as part of our shared natural landscape.

There has been travel and exploration along rivers, shorelines, coastlines, over treacherous rapids, and across oceans. Clans of Native Americans from time eternal. Fur trappers and mountain men in the Rocky Mountains. Lewis and Clark and their Expedition, the “Corps of Volunteers for North Western Discovery.” The eyes of Westward expansion brought the waterways into an ever-expanding focus.

Glaciers and mountain snowpacks, alpine lakes and streams, mountain ranges, and watersheds that supply old and new communities. These were the High Places, and they too felt the trod of rawhide snowshoes; the trek of the Klondike mule and packhorse teams; the plying of paddle from hands that directed a canoe; the whistle of steamboats, as these brought new commerce and transportation and trade up and down the Ohio, the Missouri, and the Mississippi rivers. Through these ecosystems, spawning salmon, spotted trout, and other fish; moose, beavers, birds, bears, from the tiniest midges to the largest carnivores, water was plentiful and precious.

Through paintings of the American West, we can see the waters of our past as they once were: lakes and streams, geothermal hot springs, waterfalls, winding rivers untouched and undiminished by human habitation, passage, or presence. The beauty, the integrity, of these waters and lands beckoned to new arrivals, while remaining the treasured home of those already here.

George Catlin, a prolific American painter of the early 19th century, sought to ensure that these scenes and their locations he encountered in his travels were a visual record for future generations. In Catlin’s own time, his painting of Niagara Falls (1827) emerged as a clear example of human impact upon the natural landscape. The artist provided a written record of his travels, and published these in 1841 as Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians. It heralded a call to act, in order to save such places under a new parks-focused identity.

Further efforts to save such landscapes ultimately led to the passage of the National Parks Act on March 1, 1872, which established the first of these “national parks” — Yellowstone National Park. Majestic waterfalls and valley lakes inspired the brushwork of Catlin and others, including Hudson River School painter Thomas Moran (The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone) and Albert Bierstadt (Valley of the Yosemite). A pattern was thus established: Yosemite was one of three, new designated National Parks in 1890, with others following in rapid succession. The dawn of the National Park Systems brought with it the promise of lasting protections for the nation’s landscapes.

George Catlin. View in the Cross Timbers. 1872

Creative photography soon added new dimensions of realism to the parks and the waters, through the efforts of photographers such as Ashael Curtis or environmentalist Ansel Adams, who collectively helped to further imbue these places within the American consciousness.

"Kearsarge Pinnacles, Kings River Canyon (Proposed as a national park)," California, 1936.; From the series Ansel Adams Photographs of National Parks and Monuments, compiled 1941 - 1942, documenting the period ca. 1933 - 1942.

The waters remained an integral part of the National Parks and the National Forests, flowing freely within and throughout their borders. Yet these too, came under strain from expansion, increased use, more demanded as a resource. Hydroelectric impacts became commonplace on water ecosystems, with the construction of new dams providing power, but submerging whole communities, rivers, falls (note for Washington state: Celilo Falls on the Columbia River, lost in 1957). Further Challenges in the 20th century have abounded, from pollution, human encroachment & over-usage, to the impact of water rights and supplies siphoned off on rivers, like the Colorado. Add to these the surgency of invasive water species, plants, snails, and fish (the Great Lakes); and global climate changes, with a correlating increase in retreating glaciers, diminished annual snowpacks, and rising sea levels. The parks have begun to emerge as oases of conservation made timely, but increasingly isolated as bastions of protected views.

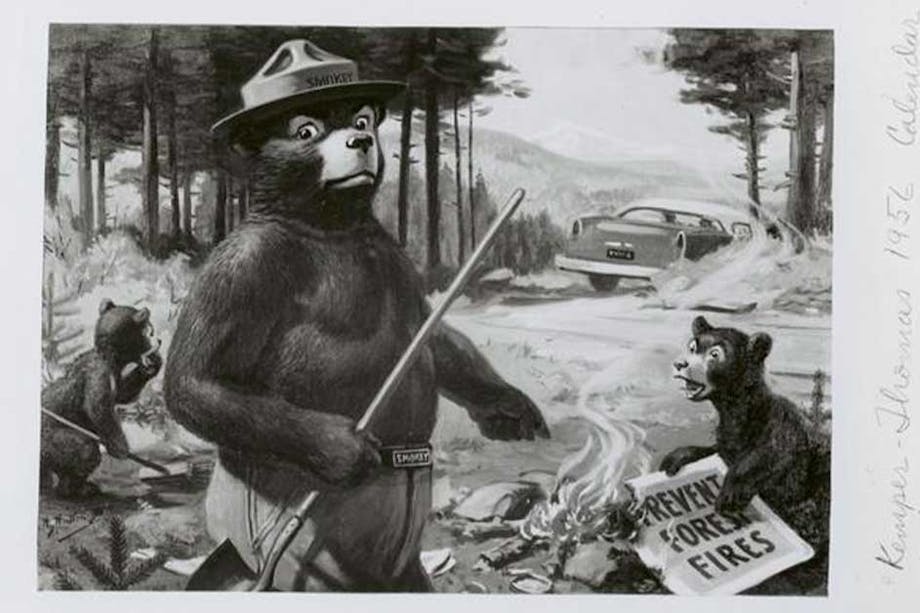

Supplementing the parks, were special designated “national forests” which today number 154 protected lands covering just shy of 2 million acres across the United States. The first of these followed on the heels of the first National Park, with the establishment of the Yellowstone Park Timber and Land Reserve, March 30, 1891. The Forest Reserve Act of 1891, followed by the Transfer Act of 1905, helped to further expand forest reserves as protected lands within the public domain.

It has all not been for naught. Instilling environmental safeguards, laws, and protections, that focus on preservation and protection of water in the environment. New efforts with The Clean Water Act, and cleanup of Superfund sites by the Environmental Protection Agency, engagement with Native American tribes, whose lands have seen dams over rivers, and how these may be removed like the one on the Elwha River in Olympic National Park in 2012. These are actions of necessity, but began with an Act of creation that led to the National Parks across the United States.

Water marks the passage of time, etching and altering the very landscapes through which it flows. As a people, we remain subject to the courses it takes, leading us to home, to distant lands, or, to remain fixed in one place.